Navigating the Gray Area: Understanding Situationships and Their Emotional Impact

Table of Contents

Introduction: The Confusing In-Between

It started innocently enough. Maybe it was a Friday night drink after work, laughter spilling over the rims of two coffee cups, or a weekend road trip where everything felt effortless. You share texts late into the night, you meet up without planning, and for a moment, it feels like more than friendship—but no one ever says the words “we’re dating.”

This is the territory of a situationship: a gray zone between friendship and committed romance. Many people stumble into it without fully realizing the emotional consequences. On the surface, it can feel liberating—no labels, no pressure—but underneath, it often fosters confusion, insecurity, and unspoken expectations. Understanding why situationships form, how they operate psychologically, and what strategies exist for navigating them can save countless hours of emotional turmoil.

Situationships are far more common than most admit. In our era of dating apps, social media, and shifting norms around commitment, the lines of intimacy have blurred. Recognizing the signs and the psychology behind them isn’t about judgment—it’s about reclaiming clarity and emotional agency.

What Exactly Is a Situationship?

At its core, a situationship is a romantic or semi-romantic relationship without clear boundaries, definitions, or long-term commitment. Unlike traditional dating, where the trajectory is often apparent, situationships float in ambiguity. Partners may enjoy each other’s company, share physical intimacy, and even invest emotionally, but the rules of engagement are undefined.

What makes a situationship tricky is the contrast between intimacy and uncertainty. You might text every day, spend weekends together, or even meet each other’s families, but the lack of a defined commitment creates a persistent emotional tension. It’s the “almost-but-not-quite” phenomenon that can leave one partner hopeful and the other nonchalant, or sometimes, both people quietly holding onto the uncertainty.

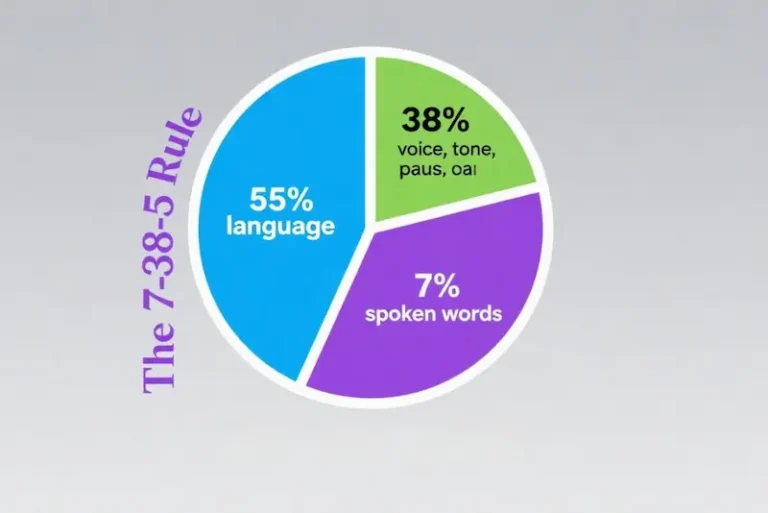

From a psychological perspective, situationships thrive in ambiguity. Behavioral economists call this a type of intermittent reinforcement, a principle borrowed from B.F. Skinner’s studies on reward schedules. When affection, attention, or validation arrives inconsistently, the brain releases dopamine unpredictably, making the connection surprisingly compelling—and occasionally addictive. This is why people often find themselves deeply attached despite the absence of commitment.

Real-Life Scenarios: How Situationships Manifest

To understand the emotional dynamics, it helps to examine real-life examples:

Scenario One: The Office Connection

Emma and Alex work in the same department. They go to lunch together almost daily, share jokes during meetings, and occasionally grab drinks after work. Everyone at the office senses a spark, but they never explicitly define the relationship. Alex texts late at night, sometimes flirty, sometimes distant. Emma finds herself analyzing every word and emoji. She likes Alex, but she also feels anxious because she isn’t sure where she stands.

Here, the lack of explicit commitment is emotionally taxing. The ambiguity fuels attachment but also fosters insecurity. Emma’s mind constantly tries to predict Alex’s feelings, a process called cognitive rumination, which psychologists link to anxiety and depressive symptoms when prolonged.

Scenario Two: The Weekend Romance

Jordan and Mia meet through mutual friends. Their weekends are filled with fun outings, physical intimacy, and deep conversations. During the week, they barely communicate. There’s no label, no expectation beyond what happens in person. Jordan enjoys the flexibility; Mia finds herself wishing for more consistent connection.

In this scenario, the imbalance of needs—one partner craving stability, the other enjoying freedom—creates subtle emotional friction. Psychologists often refer to this as attachment mismatch. People with anxious attachment styles may over-invest in situationships, seeking reassurance, while those with avoidant tendencies prioritize autonomy, keeping distance.

These examples highlight a central truth: situationships are not inherently “bad” or “toxic,” but their psychological dynamics can produce unintended stress and confusion if left unexamined.

The Psychological Mechanics Behind Situationships

Situationships tap into several core human psychological mechanisms. Understanding these can help explain why they feel so compelling yet so frustrating.

1. Intermittent Reinforcement and Dopamine

As mentioned earlier, inconsistent attention triggers intermittent reinforcement—a principle where rewards appear unpredictably. Neuroscientifically, these unpredictable bursts of validation release dopamine in the brain, reinforcing behaviors and emotional investment. This is the same principle behind gambling, social media notifications, and even casual friendships that leave you “hooked” on responses.

When one partner showers attention sporadically, the other can become psychologically invested, constantly seeking the next moment of affirmation, which creates a subtle but powerful cycle of longing.

2. Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) and Ambiguity

Ambiguity in relationships activates loss aversion, a concept from behavioral economics suggesting that humans feel potential losses more intensely than equivalent gains. In a situationship, the uncertainty of whether the other person might “disappear” keeps individuals tethered, often longer than they would stay in a clearly defined relationship that might eventually end.

This fear can amplify emotional highs when interactions go well, and emotional lows when responses are delayed or distant, creating a rollercoaster of attachment and anxiety.

3. Attachment Styles and Relational Patterns

Attachment theory, developed by John Bowlby and later expanded by Mary Ainsworth, provides a lens to understand why some people are drawn into situationships. Individuals with anxious attachment tend to over-invest, seeking clarity and reassurance, while avoidant types maintain emotional distance, valuing autonomy. When these styles meet in a situationship, the resulting tension often mirrors the “push-pull” dynamic: one partner wants closeness, the other prefers flexibility, producing repeated cycles of connection and withdrawal.

4. The Illusion of Choice

Situationships can create the perception of freedom and autonomy, which is psychologically attractive. People convince themselves they can exit at any time, but the emotional investment often overrides this rational thought. The paradox of choice—wanting multiple possibilities while struggling with commitment—further complicates emotional clarity.

Essentially, situationships exploit natural human tendencies for reward-seeking, attachment, and risk aversion, making them simultaneously thrilling and exhausting.

Practical Strategies for Navigating Situationships

Knowing the psychological mechanics is one thing. Applying that knowledge to your emotional life is another. Here’s how you can approach situationships with clarity and self-respect:

Recognize Your Emotional Needs

Start by asking yourself what you genuinely want. Are you comfortable with ambiguity? Do you desire long-term commitment or more casual connection? Writing down your emotional priorities helps identify whether the situationship aligns with your needs or silently undermines them.

Communicate Your Boundaries

Even in informal relationships, expressing preferences and limits matters. Instead of waiting for labels, clarify what feels emotionally sustainable. For example, “I enjoy spending time with you, but I need consistency to feel secure,” communicates your needs without demanding a label.

Observe Behavioral Patterns

Actions reveal more than words. Does your partner make time for you, show empathy, and demonstrate respect for your boundaries? Monitoring consistent behavior can help distinguish a healthy flexible connection from one that triggers anxiety and self-doubt.

Manage Expectations

Situationships often fail when expectations are unspoken or mismatched. By mentally separating hope from reality, you can protect your emotional energy. Recognize that unpredictability is inherent, and accept that certain frustrations may be unavoidable.

Prioritize Self-Validation

Situationships can subtly erode self-worth if you rely on the other person for emotional security. Cultivating self-validation—through hobbies, friendships, and personal growth—ensures that your sense of value doesn’t hinge on external affirmation.

Decide on Action

Sometimes, the healthiest step is to redefine or exit the situation. It might mean requesting clarity, limiting engagement, or ending the connection if it consistently undermines your emotional well-being. It’s not a failure; it’s an exercise in emotional integrity.

Long-Term Implications of Situationships

Repeatedly engaging in situationships without reflection can have subtle long-term effects. Chronic uncertainty may reinforce anxious attachment patterns, while repeated experiences of emotional inconsistency can influence self-esteem and relationship expectations. However, when approached thoughtfully, situationships can also provide opportunities to:

- Explore personal boundaries and attachment tendencies.

- Learn communication skills in emotionally gray contexts.

- Understand what you value most in a committed relationship.

Viewed through this lens, situationships are less about “good” or “bad” and more about what they reveal about human desires, insecurities, and the way we navigate intimacy.

Conclusion: Finding Clarity Amid Ambiguity

Situationships exist in the liminal space of modern relationships—sometimes exciting, often confusing, and always instructive. They expose our attachment patterns, challenge our emotional boundaries, and test our capacity for self-awareness. The key isn’t to avoid them entirely but to engage consciously.

By observing our emotional responses, communicating openly, and maintaining self-respect, we can navigate these gray zones without losing ourselves. Clarity comes not from forcing labels, but from understanding what we truly need, recognizing patterns, and choosing consciously how we invest our time and heart.

Situationships are mirrors—reflecting both what we crave and what we fear. Approached with insight, they can teach us not only about others but also about the way we relate to ourselves.