Learned Helplessness: What It Is, Causes, and How to Overcome It (Psychology Guide)

Have you ever felt like no matter how hard you try, your efforts just don’t pay off? Maybe you studied for weeks for a college exam, only to get a low grade—and then stopped trying to prepare for the next one. Or perhaps you kept pitching new ideas at work, but none were approved, so you stopped contributing altogether. If this “why bother?” feeling sticks around, you might be dealing with a psychological phenomenon called Learned Helplessness.

This concept isn’t just a “bad mood”—it’s a well-documented pattern that affects millions of Americans, from students struggling in school to professionals burnt out at work. Let’s break down what Learned Helplessness is, why it happens, and most importantly, how to overcome it.

What Is Learned Helplessness? (Psychological Definition)

Learned Helplessness is a psychological state where people (or animals) stop trying to change their circumstances after repeated exposure to uncontrollable negative events. They come to believe “nothing I do matters”—even when opportunities to improve arise.

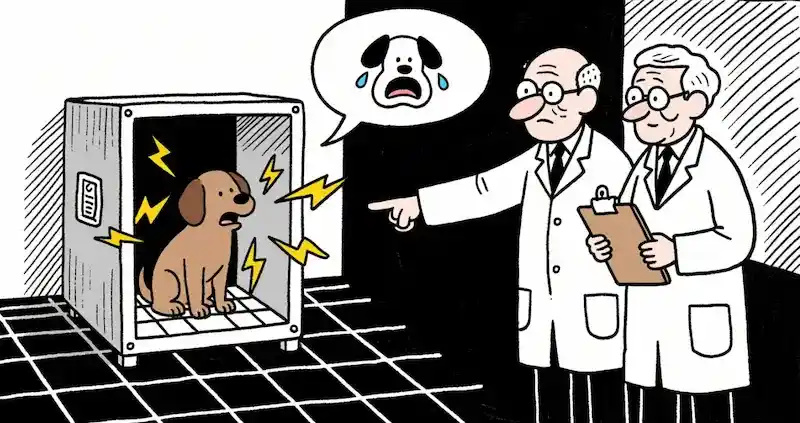

The term was first coined by American psychologist Martin Seligman in 1967, during a series of now-famous experiments at the University of Pennsylvania. Seligman’s work laid the groundwork for understanding how repeated failure shapes our sense of control—and it all started with dogs.

Seligman’s Classic Learned Helplessness Experiment

Seligman’s team placed dogs in a small metal cage with a low electric current. When a tone played, the cage floor would deliver a mild shock. At first, the dogs tried to escape: they jumped, barked, and scrambled to find a way out. But after several rounds of shocks with no escape, something shifted.

Even when the researchers opened the cage door (giving the dogs a clear path to safety), the dogs stopped trying. They just lay down in the cage, whimpering, and waited for the shock to end. They had learned that their actions couldn’t change the outcome—and that belief kept them trapped, even when freedom was possible.

How Learned Helplessness Shows Up in Humans

Seligman later extended his research to humans, and the results were striking. Learned Helplessness doesn’t just happen in labs—it plays out in everyday life, often in subtle ways. Here are common examples American readers will recognize:

- A high school student who fails math tests repeatedly starts skipping class, thinking “I’m just bad at math, so why try?”

- A new employee who’s criticized for their first few projects stops sharing ideas, convinced “I’ll just mess it up again.”

- A person who tries to lose weight multiple times (with no long-term success) gives up on exercise and healthy eating, saying “I’ll always be overweight.”

The 4 Stages of Learned Helplessness

Learned Helplessness doesn’t develop overnight—it builds in four distinct stages, according to Seligman’s later research (published in his 1992 book Learned Optimism):

- Experiencing uncontrollable failure: You try hard at a task (e.g., applying for jobs, learning a skill) but keep failing, leading to frustration or sadness.

- Forming a “no control” belief: You start thinking, “My efforts don’t affect the result.” For example, a job seeker might say, “I’ll never get hired, no matter how good my resume is.”

- Developing helplessness: You feel powerless to change your situation. Your motivation drops, and you stop setting goals—why bother if you’ll just fail?

- Generalizing the helplessness: The feeling spreads to other areas of life. A person who feels helpless at work might stop trying to fix a strained relationship, thinking “I can’t make anything better.”

What Causes Learned Helplessness? (4 Key Factors)

Learned Helplessness isn’t a flaw in your character—it’s a response to specific life experiences. Research from the American Psychological Association (APA) identifies four main causes, all of which are common in U.S. culture (where “success” is often emphasized, and failure is stigmatized).

1. Repeated Uncontrollable Failure

The most direct cause of Learned Helplessness is repeated failure with no way to change the outcome. This is especially common in environments where success depends on factors outside your control.

For example:

- A college student taking a class with a “curve” where only 10% of students get an A—even if they study 20 hours a week, they might still fail to top the class. Over time, they stop trying.

- A retail worker who’s told “meet this sales quota or get fired”—but the store has low foot traffic, so no matter how hard they pitch products, they can’t hit the number. Eventually, they stop putting in extra effort.

Seligman’s research shows that it’s not just failure itself that causes helplessness—it’s the feeling that you can’t control the failure. If you have even a small sense of control (e.g., “I can ask the professor for extra help”), you’re less likely to develop the pattern.

2. Negative Attribution Styles

How you explain failure to yourself—your attribution style—plays a huge role in Learned Helplessness. People who develop helplessness tend to blame themselves in three unhelpful ways (what psychologists call the “3 Ps”):

- Personal: “I failed because I’m stupid/lazy/untalented” (instead of “I failed because I didn’t have enough time”).

- Permanent: “I’ll always fail at this” (instead of “This time was hard, but next time I can try differently”).

- Pervasive: “I’m bad at everything” (instead of “I’m bad at this one thing”).

This style is common in the U.S., where individualism often leads people to take full responsibility for failure—even when external factors (like a lack of resources) are to blame. For example, a freelance writer who can’t land clients might think “I’m a terrible writer” (personal, permanent, pervasive) instead of “There’s a lot of competition right now” (external, temporary, specific).

3. Chronic Negative Feedback

The people around you—teachers, bosses, family, friends—shape how you see your ability to control outcomes. If you’re constantly hit with criticism or dismissal, you’re far more likely to develop Learned Helplessness.

Consider these U.S.-centric examples:

- A child whose parent says “You’ll never get that sport right” every time they miss a shot.

- An employee whose manager responds to every idea with “That won’t work” without explanation.

- A friend who laughs at you for trying to learn a new hobby, saying “You’re not creative enough.”

Over time, this feedback becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. You start to believe the negative messages—and stop trying to prove them wrong. A 2021 study in the Journal of Applied Psychology found that U.S. workers who received “unconstructive criticism” (e.g., no advice for improvement) were 3x more likely to report feelings of helplessness than those who got specific, supportive feedback.

4. Low Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy—a term coined by psychologist Albert Bandura—refers to how confident you are in your ability to complete a task. People with low self-efficacy think “I don’t have the skills to do this,” so they avoid challenges. This makes them more likely to develop Learned Helplessness.

In the U.S., low self-efficacy often ties to comparisons—thanks to social media, where people tend to share only their “wins.” For example:

- A new parent sees other moms on Instagram posting “perfect” homemade meals and clean houses. They try to keep up but fail, so they think “I’m a bad parent” (low self-efficacy) and stop trying to cook or clean regularly.

- A recent grad sees classmates getting high-paying jobs on LinkedIn. They apply to dozens of roles but get rejected, so they think “I’m not qualified for anything” and stop applying.

Low self-efficacy and Learned Helplessness feed off each other: low confidence leads to giving up, and giving up reinforces low confidence.

How to Overcome Learned Helplessness (5 Actionable Steps)

The good news? Learned Helplessness is learned—which means it can be unlearned. The key is to rebuild your sense of control, one small step at a time. Below are evidence-based strategies, tailored to U.S. readers (e.g., busy schedules, focus on practicality).

1. Break Goals Into “Micro-Wins” (Start Small)

Big goals (e.g., “Get a promotion,” “Lose 30 pounds”) can feel overwhelming—especially if you’re used to failing. Instead, split them into tiny, achievable tasks that take 5-15 minutes. These “micro-wins” build confidence and prove to yourself that your actions do matter.

Examples for U.S. readers:

- If you want to improve at work: “Write one bullet point for my project update today” (instead of “Finish the entire report”).

- If you want to exercise more: “Walk around the block once after lunch” (instead of “Go to the gym for an hour”).

- If you want to learn a skill: “Watch one 10-minute YouTube tutorial on Excel” (instead of “Master Excel this week”).

Each micro-win releases dopamine (the “reward chemical” in your brain), which motivates you to keep going. A 2020 study from Harvard Business School found that people who tracked micro-wins were 76% more likely to achieve long-term goals than those who focused only on big milestones.

2. Track Progress (Don’t Just Focus on Results)

Learned Helplessness makes you fixate on “failure” (e.g., “I didn’t get the job”) instead of the effort you put in (e.g., “I applied to 5 jobs this week”). To counter this, keep a “progress journal”—physical or digital—where you write down one thing you did each day, even if it’s small.

What to track:

- Actions: “I emailed my professor to ask for help with math.”

- Effort: “I studied for 30 minutes, even though I didn’t feel like it.”

- Small wins: “I got a response from the job I applied to—they want an interview!”

This journal helps you reframe your thinking: instead of “I never succeed,” you’ll see “I’m taking steps, and some are working.”

3. Practice “External + Temporary” Attribution

Remember the “3 Ps” (personal, permanent, pervasive) that fuel Learned Helplessness? To unlearn it, you need to replace those with external, temporary, specific explanations for failure.

Let’s use examples to see how this works:

| Old (Helpless) Attribution | New (Empowering) Attribution |

|---|---|

| “I didn’t get the job because I’m unqualified.” (Personal, Permanent) | “I didn’t get the job because they were looking for someone with 5 years of experience, and I have 3. Next time, I’ll apply to roles that match my experience.” (External, Temporary, Specific) |

| “I failed the exam because I’m bad at math.” (Personal, Pervasive) | “I failed the exam because I didn’t study the algebra section enough. I’ll focus on algebra this week and retake the test.” (Specific, Temporary) |

| “My friend didn’t text back because they hate me.” (Personal, Permanent) | “My friend didn’t text back because they’re busy with their new job. I’ll check in again tomorrow.” (External, Temporary) |

This isn’t “making excuses”—it’s being honest about what you can and can’t control. The APA recommends practicing this attribution style for 2-3 weeks; over time, it becomes automatic.

4. Build Habits That Boost Control (Even Small Ones)

Learned Helplessness thrives when you feel like you have no control over your life. To fight back, build small habits that give you a sense of mastery—things you can do every day, no matter how busy you are.

Examples tailored to U.S. lifestyles:

- Morning routine: Pick one small action to do first thing—make your bed, drink a glass of water, or stretch for 2 minutes. This starts your day with a “win.”

- Skill-building: Learn one tiny skill each week—e.g., “tie a tie,” “make scrambled eggs,” “use a new Excel function.” Mastering small skills builds confidence.

- Time blocking: Schedule 15 minutes a day to work on something you care about (e.g., writing, painting, learning a language). This gives you control over how you spend your time, even if the rest of your day is busy.

These habits might seem trivial, but they add up. A 2018 study in Psychological Science found that people who did one “control-building” habit daily for 4 weeks reported a 40% decrease in feelings of helplessness.

5. Seek Support (It’s Not a Sign of Weakness)

In the U.S., there’s often a stigma around “asking for help”—but it’s one of the most powerful ways to overcome Learned Helplessness. Support can come from three places:

- Trusted friends or family: Talk to someone who knows you well and will give you honest, supportive feedback. For example, say “I’ve been feeling like I can’t get anything right at work—can you help me see what I’m doing well?”

- Mentors or coaches: A work mentor, school counselor, or life coach can give you specific advice to improve. Many U.S. workplaces offer free coaching through Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs)—take advantage of it.

- Mental health professionals: If feelings of helplessness are affecting your sleep, work, or relationships, a therapist can help. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is especially effective for Learned Helplessness—it teaches you to reframe negative thoughts and build coping skills. According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), CBT reduces symptoms of helplessness in 70-80% of people who try it.

Remember: Asking for help means you’re taking control—not giving up.

Real-Life Example: Overcoming Learned Helplessness in the U.S. Workplace

To make this concrete, let’s look at a real (anonymized) story from a U.S. professional:

Sarah, a 28-year-old marketing associate in Chicago, spent 6 months trying to pitch new campaign ideas to her manager. Every time, her manager said “No—we’re sticking with what works.” After the 7th rejection, Sarah stopped contributing. She thought “My ideas are terrible, and I’ll never get promoted.” She started showing up late, missing deadlines, and feeling hopeless—classic Learned Helplessness.

Then Sarah tried two strategies:

- Micro-wins: Instead of pitching a full campaign, she started sharing 1-sentence “quick ideas” in team meetings (e.g., “What if we post a Reel about our new product?”). After 3 weeks, her manager said “That’s a good thought—let’s test it.”

- Mentorship: She asked a senior colleague to review her past campaign ideas. The colleague said “Your ideas are strong—they just don’t align with our current budget. Let’s tweak one to fit.”

Within 2 months, Sarah’s “tweaked” idea was approved, and the campaign drove a 20% increase in sales. She started contributing again, and 6 months later, she got a promotion.

Sarah’s story shows that Learned Helplessness isn’t permanent—small, intentional steps can break the cycle.

Summary

Learned Helplessness is a common psychological pattern where repeated uncontrollable failure leads you to believe “nothing I do matters.” It’s caused by factors like negative feedback, unhelpful attribution styles, and low self-efficacy—but it’s not permanent. By focusing on micro-wins, tracking progress, reframing failure, building control through habits, and seeking support, you can rebuild your sense of agency.

Remember: The “helpless” feeling isn’t a reflection of your abilities—it’s a learned response, and learned responses can be unlearned. Every small step you take to regain control is a step away from helplessness and toward the life you want.

CTA (Call to Action)

- If you’ve struggled with Learned Helplessness, share your story in the comments below—your experience could help someone else feel less alone.

- And if feelings of helplessness feel overwhelming, reach out to a mental health professional—organizations like the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) offer free resources for U.S. residents (visit nami.org for more info).

You don’t have to feel stuck forever—you have more control than you think.