Franklin Effect: How to Make Someone Like You (Pro Tips for Dating & Relationships)

Table of Contents

Imagine this: You’re at your office in Chicago, and a coworker asks if you can quickly review their client presentation slides. You say yes, spend 10 minutes giving feedback, and move on with your day. A week later, you notice that same coworker stops by your desk to share a free coffee or update you on their project—suddenly, you feel more connected to them than before.

Or maybe you’re at a local book club in Austin, and a new member asks to borrow your copy of a rare Toni Morrison novel. You lend it, and when they return it with a handwritten note thanking you, you find yourself looking forward to their next comment in the group.

Why does this happen? Why do small favors lead to closer bonds—even when you were the one helping? The answer lies in a powerful psychological phenomenon called the Franklin Effect—and it’s one of the most underrated tools for building relationships, whether platonic or romantic.

What Is the Franklin Effect?

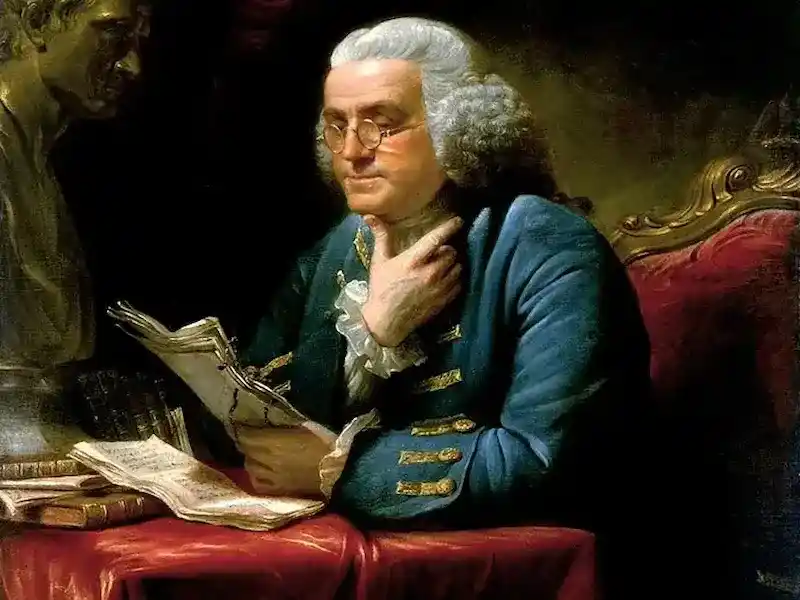

The Franklin Effect isn’t just a “life hack”—it’s a well-documented psychological pattern with roots in American history. The story starts with Benjamin Franklin, one of the U.S. Founding Fathers, during his time serving in the Pennsylvania State Legislature.

Franklin had a fierce political rival who constantly opposed his ideas and spoke out against him in meetings. Instead of arguing or avoiding the rival, Franklin took a different approach: He heard the man owned a rare, out-of-print book on history, so he sent a polite letter asking to borrow it. To Franklin’s surprise, the rival agreed. A week later, Franklin returned the book with a detailed thank-you note highlighting how much he’d learned from it.

The next time they crossed paths, the rival greeted Franklin warmly—something he’d never done before. Over time, the two became allies, and the rival even advocated for Franklin’s policies later on.

From a psychological perspective, the Franklin Effect can be defined as: People who have helped you once are more likely to help you again in the future—and they often develop more positive feelings toward you in the process, compared to people you’ve helped.

This flips the common myth that “giving favors makes others like you more.” Instead, it’s the act of receiving help (and the giver’s internal justification for it) that drives connection—a dynamic that plays out every day in American workplaces, dating scenes, and social circles.

The Psychology Behind the Franklin Effect

To use the Franklin Effect effectively, you need to understand why it works. Two key psychological theories explain its power—and both are backed by research from top U.S. institutions.

1. Cognitive Dissonance Theory

Cognitive dissonance is the mental discomfort we feel when our actions conflict with our beliefs. Psychologist Leon Festinger, a pioneer in social psychology (and a former Stanford University professor), first proposed this theory in the 1950s—and it’s the foundation of the Franklin Effect.

Here’s how it applies: When someone agrees to help you (e.g., a classmate at UCLA helps you edit a paper, or a neighbor in Detroit helps you fix a flat tire), they ask themselves: “Why would I spend my time helping this person?”

Most people don’t want to see themselves as “someone who wastes time on people they don’t like.” To resolve this discomfort, they adjust their beliefs: “I must like this person, or they’re worth my time—otherwise, I wouldn’t have helped them.”

Over time, this belief becomes stronger. The more small favors someone does for you, the more they convince themselves they like you—and that conviction shows in their actions (e.g., initiating conversations, offering more help).

A 2019 study published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology (a leading U.S.-based journal) confirmed this: Participants who were asked to do a small favor for a stranger reported 30% higher positive feelings toward that stranger than those who received a favor instead.

2. Sense of Self-Worth

Helping others also boosts the giver’s self-esteem—and that positive feeling gets tied to you.

When you ask someone for help (e.g., “Can you recommend a good yoga studio in Denver?” or “How do you use this spreadsheet tool at work?”), you’re sending them a subtle message: “I trust your judgment. I think you have something valuable to offer.”

This validation triggers a release of dopamine (the “feel-good” chemical) in the brain, as noted in a 2022 Harvard Business Review study. The giver associates that positive feeling with you—and wants to repeat it by interacting with you more.

Think about it: If a friend asks you to help them plan a birthday party (and you love event planning), you’ll likely feel proud that they recognized your skill. Later, when you see them, you’ll remember that pride—and feel more warmth toward them as a result.

How to Use the Franklin Effect in Real Life

The Franklin Effect isn’t about manipulating people—it’s about creating genuine, mutual connections. Below are actionable ways to apply it in three key areas of life, tailored to American social norms.

1. Expanding Your Social Circle

Making new friends as an adult in the U.S. can feel tough—whether you’re new to a city or just looking to meet people with similar interests. The Franklin Effect simplifies this by giving you a natural way to start conversations.

Here’s how to use it:

- Choose low-pressure favors tied to shared interests: If you’re at a community hiking group in Seattle, ask an active member, “I’m new to this trail—do you have a favorite spot to stop for water?” If you’re at a craft fair in Nashville, say to a vendor, “Your pottery is amazing—do you have a tip for someone just starting to work with clay?”

- Follow up with specific gratitude: Don’t just say “thanks”—be specific. For example, “That water spot you mentioned saved me from running out—thank you!” Specificity shows you paid attention and valued their help.

- Offer a small return later: If they recommended a hiking spot, share a photo of your trip with them. If they gave you a craft tip, bring them a small homemade snack next time. This keeps the interaction balanced and builds trust.

A 2023 survey by the Pew Research Center found that 62% of U.S. adults say “shared activities” are the best way to make friends—and the Franklin Effect turns those activities into connection opportunities.

2. Using the Franklin Effect for Dating

If you’re interested in someone (a crush, a casual date, or someone you’ve been flirting with), the Franklin Effect can help bridge the “awkward gap” and make them feel more invested in you.

The key here is to ask favors that let them share their interests—this shows you care about them, not just getting them to like you.

Try these examples:

- If they love vinyl records: “I want to start collecting jazz vinyl—do you have a favorite album I should buy first?”

- If they’re into cooking: “I’m trying to make pasta from scratch—do you have a go-to recipe for tomato sauce?”

- If they’re a movie buff: “I heard you love indie films—what’s one I should watch this weekend?”

Why this works: When they share their interests, they’re not just “helping you”—they’re sharing a part of themselves. A 2021 study in Personal Relationships (a journal published by the International Association for Relationship Research) found that people feel more attracted to others who show genuine interest in their passions.

Pro tip: Avoid big or personal favors early on. Asking to borrow their car or help you move is too much—stick to small, low-stakes requests. You want them to feel good about helping you, not stressed.

3. Building Workplace Relationships

The workplace is where the Franklin Effect often works best—especially if you’re a new employee or looking to collaborate with colleagues you don’t know well. It helps you avoid the “lonely new kid” feeling and build a network of allies.

Here’s how to apply it:

- Ask for learning-related favors: New to a team in New York? Say to a senior colleague, “Can you walk me through how we format client reports here? I want to make sure I get it right.” This shows you’re proactive (not lazy) and values their expertise.

- Say thank you publicly (when appropriate): If a colleague helps you with a project that impresses your boss, mention their help in a team meeting: “I couldn’t have finished that presentation without Sarah’s help—she explained the client’s needs perfectly.” Public recognition boosts their self-esteem and makes them more likely to help you again.

- Repay with small, consistent gestures: If they help you with a report, grab them a coffee the next morning. If they walk you through a software tool, offer to take notes for them in the next team meeting. These small acts build a “favor bank” that strengthens your relationship over time.

A 2024 study by Gallup found that U.S. employees who have strong workplace relationships are 50% more productive—and the Franklin Effect is a simple way to build those bonds.

Common Mistakes to Avoid with the Franklin Effect

The Franklin Effect is powerful, but it can backfire if you use it the wrong way. Here are three mistakes to steer clear of:

- Asking for too much too soon: A stranger at a coffee shop won’t help you plan your entire vacation—start with a small ask like, “What’s your favorite drink here?” Pushing for big favors makes you seem entitled, not friendly.

- Forgetting gratitude: If someone helps you and you don’t say thank you, they’ll feel unappreciated. Gratitude is the glue that turns a one-time favor into a relationship. Even a quick text works!

- Using it manipulatively: If you only ask for favors to “trick” someone into liking you, they’ll notice. The Franklin Effect works because it’s genuine—you need to be interested in them, not just what they can do for you.

Final Thoughts on the Franklin Effect

The Franklin Effect is a reminder that relationships aren’t just about giving—they’re about mutual vulnerability. Asking for help doesn’t make you weak; it shows you’re human, and it gives others a chance to feel valued.

Whether you’re trying to make new friends in Phoenix, connect with a crush in Boston, or build allies at work in Los Angeles, the Franklin Effect works because it’s rooted in basic human psychology: We like people who make us feel good about ourselves.

As Dr. Susan Campbell, a U.S.-based relationship psychologist and author of Getting Real, puts it: “Genuine requests for help create a bridge between two people. When someone helps you, they’re not just doing a favor—they’re investing a little piece of themselves in you. And that’s the start of something real.”

Call to Action (CTA):

Have you used the Franklin Effect to build a relationship? Maybe you asked a coworker for help and became friends, or used it to connect with a crush. Share your story in the comments below—we’d love to hear how it worked for you!