Effortful Processing in Psychology: Definition, Examples, and How It Differs from Automatic Processing

Table of Contents

What Is Effortful Processing?

In psychology, effortful processing refers to encoding information into memory through conscious attention and deliberate effort. It requires mental focus, rehearsal, and awareness—making it a slower but deeper form of learning.

This concept is central to understanding how we form long-term memories and acquire new knowledge.

The effortful processing psychology definition emphasizes that this type of information processing demands active engagement. For example, when you study for an exam, memorize a speech, or learn a new language, you’re engaging in effortful processing. You must intentionally focus on the material, repeat it, and relate it to what you already know.

In AP Psychology, the definition of effortful processing is often summarized as:

“Encoding that requires attention and conscious effort, typically used for learning and remembering new information.”

Effortful processing is controlled by the brain’s prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, which manage attention and memory consolidation. It is essential for developing complex skills, mastering academics, and forming long-term understanding.

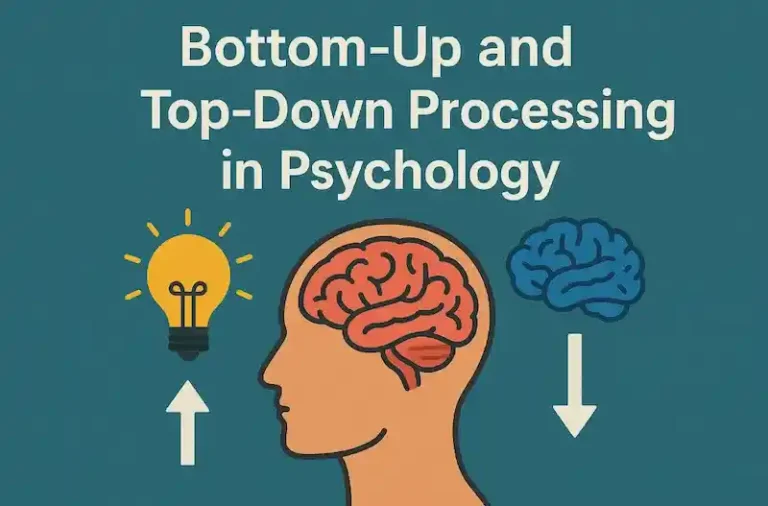

Understanding Automatic Processing

In contrast, automatic processing refers to the unconscious encoding of information—things we remember or react to without deliberate effort. The automatic processing psychology definition explains it as mental activity that happens quickly, effortlessly, and often without awareness.

When you recognize familiar faces, drive a familiar route, or read simple words without thinking, your brain is performing automatic processing. This type of cognitive processing relies on learned patterns that have become ingrained through repetition.

Automatic Processing Examples

- Reading words in your native language

- Brushing your teeth

- Driving a familiar route

- Recognizing a song after hearing just a few notes

- Typing on a keyboard without looking at the keys

These are all automatic processes examples that require little to no conscious attention. They demonstrate how practice and repetition can transform effortful tasks into automatic ones over time.

Automatic vs. Effortful Processing: The Core Differences

To understand automatic vs effortful processing, it helps to compare them directly:

| Feature | Effortful Processing | Automatic Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness | Conscious, intentional | Unconscious, effortless |

| Speed | Slow | Fast |

| Attention | Requires full attention | Minimal attention |

| Learning Stage | Early learning phase | After repetition and mastery |

| Example | Studying for an exam | Reading familiar words |

Essentially, effortful processing dominates the learning phase, while automatic processing takes over once the task is well-practiced. This transformation is at the heart of skill acquisition and habit formation.

In psychological terms, this distinction echoes Daniel Kahneman’s Dual Process Theory, where:

- System 1 (Automatic) = fast, intuitive, emotional

- System 2 (Effortful) = slow, logical, deliberate

Examples of Effortful Processing in Everyday Life

To make the concept clearer, here are several effortful processing examples from daily life:

- Learning a new language:

Memorizing vocabulary and grammar requires repetition and focus—classic effortful processing. - Studying for exams:

Students must actively rehearse information, use mnemonic devices, and test themselves to retain knowledge. - Playing a new instrument:

At first, each note and finger movement demands full attention before it becomes automatic. - Solving complex math problems:

Analytical thinking and step-by-step reasoning are effortful processes. - Public speaking:

Memorizing and practicing a speech involves active rehearsal and focus.

These examples show how conscious effort is necessary for learning something new or challenging. Over time, however, with enough practice, these tasks can become automatic.

Examples of Automatic Processing

Once a skill is mastered, it transitions into automatic processing. Here are some automatic processing examples:

- Driving while talking to a passenger

Experienced drivers can operate a car almost instinctively while their mind focuses elsewhere. - Recognizing a familiar face in a crowd

The brain automatically retrieves stored visual information. - Typing an email quickly

Years of practice allow fluent typing without thinking of each key. - Reading simple words

For literate adults, word recognition happens instantly. - Performing daily routines

Actions like showering, cooking breakfast, or locking the door require minimal thought.

These automatic processes examples illustrate how the brain conserves mental energy by automating routine tasks.

Why Effortful Processing Is Essential for Learning

Effortful processing plays a critical role in memory encoding and long-term retention. According to the Levels of Processing Theory, deeper, effortful engagement with material—such as analyzing, summarizing, or applying it—leads to stronger memory formation.

When learning something new:

- Attention directs focus on relevant stimuli.

- Rehearsal (repetition) strengthens neural connections.

- Elaboration (linking new info to prior knowledge) improves recall.

This is why cramming rarely works; without effortful engagement, information remains in short-term memory. Effective study techniques—like active recall, spaced repetition, and self-testing—all rely on effortful processing.

How the Brain Transitions from Effortful to Automatic

One fascinating aspect of cognition is how effortful tasks become automatic over time—a process known as automatization.

When you first learn a skill, the prefrontal cortex works hard to control each action. Through repetition and practice, the brain strengthens neural pathways, transferring control to more efficient regions like the basal ganglia.

This shift frees up mental resources for higher-level thinking.

Example:

- At first, learning to drive is effortful—you think about mirrors, pedals, and signals.

- After months of practice, driving becomes second nature; you can focus on conversation or navigation instead.

This transformation from effortful to automatic is the foundation of expertise in any field.

Effortful Processing in AP Psychology

In AP Psychology, effortful processing appears under the Memory Unit, often tested alongside concepts like encoding, storage, and retrieval.

Students are expected to know the effortful processing AP Psychology definition, which states:

“Encoding that requires attention and conscious effort.”

For exam preparation, understanding examples is crucial:

- Memorizing state capitals = effortful

- Recognizing your teacher’s face = automatic

Students should also note how rehearsal and semantic encoding (linking meaning) enhance effortful processing—key strategies for improving memory performance.

Automatic and Effortful Processing in Real-World Applications

Both types of processing play essential roles beyond the classroom:

Education

Teachers use effortful processing techniques—like active learning, problem-solving, and discussion—to deepen understanding. Automatic processing helps with quick recall during tests or presentations.

Skill Development

Musicians, athletes, and pilots all move from effortful to automatic stages as they master their craft. Automaticity enables performance under pressure.

Habit Formation

Behavioral psychologists emphasize that repeated effortful actions can evolve into habits through automatic processing—forming the foundation for self-discipline.

Artificial Intelligence and Cognitive Science

AI systems model similar dual processes: deep learning mimics effortful encoding, while neural networks’ pattern recognition parallels automatic processing.

Common Misconceptions

- Effortful doesn’t always mean better.

Automatic processing allows efficiency and multitasking—it’s not inferior, just different. - Automatic doesn’t mean mindless.

Many automatic responses, like emotional intelligence or driving reflexes, are highly adaptive. - You can’t skip effort.

Automaticity only comes after consistent effortful practice. Mastery demands both systems working together.

Final Thoughts: Balancing Automatic and Effortful Processing

Human cognition thrives on balance. Effortful processing fuels growth, learning, and creativity, while automatic processing ensures speed and efficiency. The goal isn’t to replace one with the other, but to move fluidly between them—knowing when to focus deeply and when to rely on intuition.

In everyday life:

- Use effortful processing to learn, reflect, and grow.

- Trust automatic processing for routine and skilled tasks.

Both are essential tools of a well-trained mind.

FAQ: Effortful vs. Automatic Processing

Q1: What is effortful processing in psychology?

Effortful processing is the encoding of information that requires conscious attention and deliberate effort, often used when learning new material.

Q2: How is effortful processing different from automatic processing?

Effortful processing is conscious and slow; automatic processing is unconscious and fast. Effortful processing builds new skills—automatic processing uses mastered ones.

Q3: What are some examples of automatic processes?

Reading familiar words, driving a known route, or typing without looking are all examples of automatic processes.

Q4: Why is effortful processing important in learning?

It leads to deeper understanding and stronger memory formation through attention, rehearsal, and meaningful engagement.

Q5: Can automatic processing be changed or unlearned?

Yes. With awareness and deliberate practice, automatic habits can be modified or replaced through new effortful learning.

AP Psychology FAQ: Answering Common Questions About Effortful & Automatic Processing

For AP Psychology students, below are answers to high-frequency questions about the two processing modes—helping you target exam preparation:

1. In AP Psychology, What Is the Relationship Between Effortful Processing and the Levels of Processing Theory?

Answer: The Levels of Processing Theory is the core theoretical support for effortful processing and a frequent AP exam topic. Their relationship is:

- Shallow Processing: Requires no effort and only processes surface features of information (e.g., a word’s color or spelling). Information is easily forgotten.

- Deep Processing: Requires effortful processing and focuses on the meaning of information (e.g., a word’s definition or connections to existing knowledge). Information is more likely to enter long-term memory.Exams may present scenarios like: “Student A memorizes words by only looking at their spellings; Student B memorizes words by using them in sentences.” You will be asked to identify which student uses effortful processing and which has better memory retention. The answer is: “Student B uses effortful processing and has better memory retention.”

2. Is Automatic Processing Innate or Learned?

Answer: Except for a few instinctive reactions (e.g., an infant’s sucking reflex or blinking), most automatic processing is learned through extensive repeated practice. AP Psychology often links “procedural memory” to automatic processing—procedural memory (e.g., riding a bike, typing) is formed when effortful processing transitions to automatic processing through repeated practice. If an exam asks, “Does automatic processing require learning?” the answer is: “Most cases require learning.”

3. How to Quickly Distinguish Between the Two Processing Modes in Exam Questions?

Answer: Focus on two clues:

- Task Proficiency: If a question describes a task as “first-time,” “unfamiliar,” or “requiring deliberate thought,” it likely tests effortful processing. If it describes the task as “proficient,” “effortless,” or “habitual,” it likely tests automatic processing.

- Attention Requirement: If a question mentions “distractions cause errors” or “requires focus,” it refers to effortful processing. If it mentions “can be done while doing other things” or “requires no attention,” it refers to automatic processing.Example question: “A proficient pianist can play music without looking at the sheet music. Which processing mode is this?” The answer is automatic processing.

4. How to Convert an Effortful Processing Task to Automatic Processing?

Answer: In AP Psychology, the core condition for conversion is “extensive, feedback-driven practice.” The specific path is:

- Clarify Task Rules: First, use effortful processing to understand the task’s steps and rules (e.g., when learning to type, first memorize which keys correspond to each letter).

- Repeat Practice: Practice for a fixed period daily to gradually reduce reliance on consciousness (e.g., typing for 20 minutes daily).

- Provide Timely Feedback: Correct mistakes during practice (e.g., if you type a wrong letter, deliberately focus on that key’s position next time) to accelerate automation.An exam question might ask: “How can students convert multiplication tables to automatic processing?” The answer is: “Through daily recitation, solving multiplication problems, and correcting errors.”

5. Is Forgetting Related to the Two Processing Modes?

Answer: Yes. The relationship mainly manifests in two ways:

- Forgetting Due to Insufficient Effortful Processing: If information is only processed shallowly (non-effortful) and does not enter long-term memory, it is quickly forgotten (e.g., forgetting a phone number after only glancing at it once).

- “Forgotten-Resistant” Automatic Processing: Procedural memory linked to automatic processing (e.g., riding a bike) is slow to forget. Even if not used for a long time, it can be quickly recovered (e.g., riding a bike again after years of inactivity).An exam question might ask: “Why can some people still ride a bike after years of not riding, but forget high school poems they memorized?” The answer is: “Riding a bike relies on automatic processing and procedural memory, which is resistant to forgetting. High school poems are often forgotten because they were not deeply processed (insufficient effortful processing) and thus not stored in long-term memory.”

References

- Craik, F. I. M., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of Processing: A Framework for Memory Research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior.

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- SimplyPsychology.org – Memory and Information Processing

MANTAP MANTAP