Doorway Effect: What It Is, Why It Happens, and How to Avoid Memory Blanks

Table of Contents

Have you ever walked into the kitchen to grab something, only to stare at the cabinets and draw a complete blank? Or headed to your home office excited to tackle a project, but sat down and forgot what you planned to do? If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone—you’re experiencing the doorway effect, a common cognitive phenomenon that affects millions of Americans daily.

Understanding this quirk of the brain isn’t just interesting; it’s practical. By learning why the doorway effect happens and how to counter it, you can cut down on frustrating memory lapses, save time, and stay focused on what matters. Let’s break down everything you need to know.

What Is the Doorway Effect?

The doorway effect is a cognitive glitch where crossing a threshold—whether a room door, office entrance, or even a hallway arch—triggers a temporary memory blank. You lose track of the task or thought you were focusing on right before the transition.

This isn’t a sign of poor memory or aging; it’s a normal function of how our brains process information. The term was first coined by Dr. Gary Small, a prominent American psychologist and director of the UCLA Longevity Center, whose research shed light on how spatial transitions impact memory.

The Science Behind the Doorway Effect (Dr. Small’s Research)

Dr. Small and his team at UCLA conducted a landmark study to document the doorway effect, using real-world scenarios that mirror everyday life. Here’s how the experiment worked:

- Participants were given simple tasks (e.g., memorizing a list of words, recalling a short sequence of numbers) in one room.

- They were then asked to walk through a door into a second room and repeat the task.

- The results were striking: 60% of participants made memory errors after crossing the threshold—forgetting words, mixing up number sequences, or losing track of the original task.

For example, a participant who memorized “milk, bread, eggs” in a living room might only recall “milk” after entering a dining room. This experiment confirmed that the act of crossing a door itself, not just time passing, disrupts memory.

Common Examples of the Doorway Effect in Daily Life

The doorway effect shows up in small, relatable moments—moments you might have brushed off as “just a brain fart.” Here are a few scenarios American readers will recognize:

- A professional grabbing a report to share with their manager, then freezing up when they reach the manager’s office door.

- A student walking to their professor’s office with a question, only to stand in the doorway with a blank mind.

- Someone heading to the garage to grab a tool, stepping through the door, and wondering why they’re there.

- A parent going to their child’s room to remind them of homework, then forgetting the reason once they enter.

These moments aren’t random—they’re all triggered by the same cognitive mechanism: the doorway effect.

Why Does the Doorway Effect Happen? (Psychological Causes)

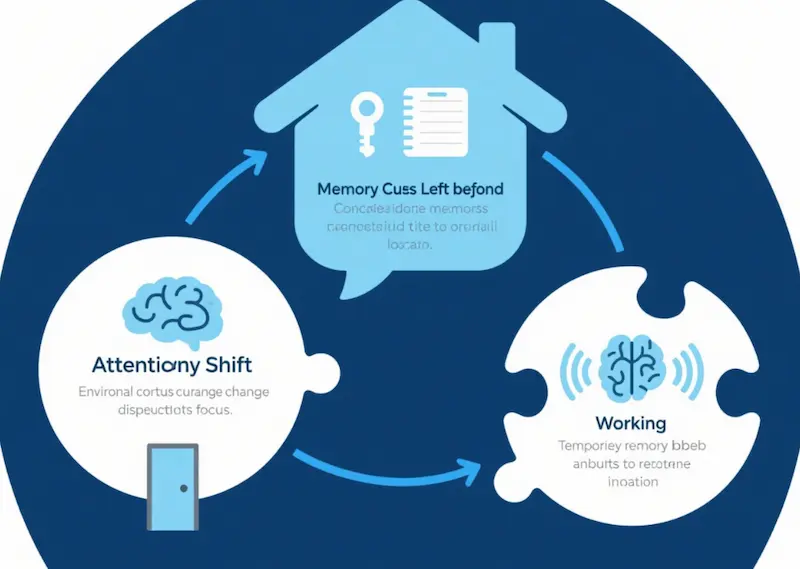

To fix the doorway effect, you first need to understand why it happens. Our brains are wired to process spatial and contextual information efficiently, but this efficiency can backfire when we switch environments. Below are the three key psychological reasons behind the phenomenon.

1. Environmental Changes Shift Your Attention

Your brain acts like a high-speed filter, constantly prioritizing new sensory information. When you walk through a door into a new space, your eyes, ears, and even sense of smell pick up fresh cues: a different room temperature, new wall art, or the sound of a coffee maker in the next room.

This shift in sensory input pulls your attention away from the task or thought you were holding. For example, if you’re heading to the kitchen to grab a spoon, your brain might fixate on the smell of cookies baking (a new sensory cue) instead of the spoon. By the time you’re in the kitchen, the original task has been pushed aside.

The American Psychological Association (APA) notes that this attention shift is an evolutionary trait—our brains evolved to prioritize new environments to keep us safe. But in modern life, it just makes us forget where we put our keys.

2. Context Switching Breaks Memory Cues

Memory isn’t stored in isolation—it’s tied to the context where you formed it. Think of context as a “memory trigger”: the chair you were sitting in, the music playing, or the light in the room. These cues help your brain retrieve information quickly.

A door acts like a “context divider.” When you cross it, you leave behind the cues that were helping you remember your task. For example:

- You’re in your bedroom folding laundry and remember to take a book to the living room. The bedroom’s bed, dresser, and laundry basket are your memory cues.

- When you walk into the living room, those cues are gone. The couch, TV, and rug are new, so your brain can’t easily retrieve the “take the book” memory.

This is why you might suddenly remember the book only when you walk back into the bedroom—your original context is restored.

3. Working Memory Has Limited Capacity

Your “working memory” is the part of your brain that holds temporary information (like “grab milk” or “call Sarah”) while you act on it. The problem? Working memory has a small capacity—think of it as a smartphone with only 1GB of RAM.

When you walk through a door, your brain has to process a flood of new information: Is this space safe? Where am I going? What’s different here? This new information “uses up” your working memory, pushing out the task you were focusing on.

For example, if you’re remembering a phone number to dial, crossing a door might make you forget it. The visual of the new room (a coffee shop, a coworker’s office) replaces the number in your working memory. The APA estimates that working memory can hold only 4-5 pieces of information at once—so new cues easily push out old ones.

How Does the Doorway Effect Impact Daily Life?

The doorway effect might seem like a minor annoyance, but over time, its impacts add up. It wastes time, slows you down, and can even fray your patience. Here’s how it affects key areas of life for American adults.

1. Wasted Time and Frustration

Small memory blanks from the doorway effect can turn a 5-minute task into a 20-minute hassle. Consider these common scenarios:

- You’re cooking dinner and walk to the pantry for salt. Once there, you forget what you need—so you go back to the stove to check. By the time you return to the pantry, you might blank again.

- You’re running errands and walk into a grocery store, only to forget half your shopping list. You either buy the wrong things or have to drive back home to check the list—wasting gas and time.

A 2022 survey by the American Productivity Association found that adults lose an average of 2.5 hours per week to “memory-related delays”—and the doorway effect is a top contributor.

2. Reduced Work Productivity

In the workplace, the doorway effect can derail focus and slow down projects. American professionals often report these issues:

- You’re in a team meeting and step out to take a quick call. When you walk back in, you can’t remember the point you were about to make—or follow the current discussion.

- You’re writing a report at your desk and walk to the printer to grab a draft. When you return, your train of thought is gone. You spend 15 minutes rereading your work to get back on track.

- You’re heading to a colleague’s desk to ask a question. At their office door, you blank—so you either ask a less important question or have to go back to your desk to remind yourself.

These delays don’t just affect you: if you’re part of a team, your blank can hold up meetings or project timelines.

3. Hindered Learning and Focus for Students

Students—from high schoolers to college undergraduates—are also hit hard by the doorway effect. Here’s how:

- A student walks from their classroom to a professor’s office hours with a question about a math problem. Once they enter the office, they can’t remember the problem details.

- A college student is studying in the library and walks to the textbook section to grab a reference. When they return to their table, they forget the specific chapter or concept they were researching.

- A high schooler heads to the counselor’s office to talk about college apps. At the door, they blank on their questions—missing a chance to get valuable advice.

These moments break learning continuity, making it harder to retain information or get help when needed.

How to Avoid the Doorway Effect (Practical Tips)

The good news? The doorway effect is manageable. With simple, science-backed strategies, you can train your brain to hold onto tasks even when crossing thresholds. Below are four actionable tips, tailored to American daily life.

1. Strengthen Memory Encoding Before You Move

“Memory encoding” is the process of “storing” a task in your brain so you can retrieve it later. To beat the doorway effect, actively encode your task before you walk through a door. Here’s how:

- Verbalize the task: Say the task out loud (even quietly) before moving. For example, if you’re heading to the kitchen for a spoon, say, “I need to grab a spoon from the silverware drawer.” Speaking engages your auditory memory, making the task harder to forget.

- Visualize the task: Picture yourself completing the task. If you’re going to your home office to send an email, imagine opening your laptop and typing the subject line. Visual cues are stronger than verbal ones for many people.

- Repeat key details: If the task has specifics (e.g., “ask Sarah about the client deadline”), repeat those details 2-3 times. Repetition reinforces the memory in your brain.

This strategy works because it makes your memory “sturdier”—so new environmental cues can’t easily push it out.

2. Use Memory Cues Tied to Your Destination

Since the doorway effect breaks old memory cues, create new ones that tie to your destination (not your starting point). Here’s how to do it:

- Pick a visual cue in the new space: Before leaving, think of a visible object in the room you’re entering. For example, if you’re going to the living room to grab a blanket, focus on the couch (a key object in the living room). Mentally link the task to the object: “Blanket is on the couch.” When you enter the living room, seeing the couch will trigger the memory.

- Use a “transition phrase”: Create a short phrase that connects the door to your task. For example, “When I open the office door, I’ll ask Mike about the budget.” Say this phrase to yourself as you walk toward the door—this links the act of crossing the threshold to your task.

- Keep a “cue object” with you: Carry a small object that reminds you of your task. If you’re heading to a meeting to discuss a project, hold the project folder in your hand. The feel of the folder will serve as a constant cue.

3. Stay Focused During Transitions

The doorway effect thrives when your attention wanders. To avoid it, stay focused on your task while crossing a door. Try these tricks:

- Minimize distractions: Put away your phone or stop talking to someone while moving. If you’re scrolling through texts or chatting about the weather, your brain can’t focus on your task—and new cues will take over.

- Plan your path: Mentally map your route before moving. For example, if you’re going from your desk to the break room to grab a water bottle, think: “Stand up, walk past Lisa’s desk, turn left at the copier, grab water from the fridge.” Having a clear path keeps your brain from fixating on new environments.

- Hold a “focus thought”: Choose one word or phrase related to your task and repeat it silently while walking. If you’re going to the garage to get a hammer, repeat “hammer” to yourself until you reach the garage. This blocks out other sensory cues.

4. Leverage Tools to Backup Your Memory

Even the best memory strategies fail sometimes—so use tools to cover your bases. These tools are easy to integrate into American daily life:

- Phone notes or reminders: Type your task into your phone’s notes app or set a 1-minute reminder before moving. For example, if you’re going to the grocery store, take a photo of your shopping list and pull it up as soon as you enter the store.

- Sticky notes in visible spots: Put a sticky note with your task on the door you’re about to cross. For example, if you’re heading to the bedroom to pack a bag for tomorrow, stick a note on the bedroom door that says “Pack gym clothes + laptop.”

- Voice memos: Record a quick voice memo with your task (e.g., “Ask Tom about the team meeting time”) and play it back when you reach your destination. This works especially well for verbal learners.

Tools like these act as “external memory” and eliminate the pressure on your brain to hold onto tasks.

Call to Action (CTA)

The doorway effect is a normal part of how our brains work—but it doesn’t have to slow you down. By understanding its causes (attention shifts, broken memory cues, limited working memory) and using practical strategies (strengthening memory encoding, using destination cues, staying focused, and leveraging tools), you can cut down on frustrating memory blanks.

Whether you’re a busy professional, a student, or someone just looking to streamline daily tasks, these tips will help you stay on track—even when crossing a door. The key is to work with your brain, not against it.

Now it’s your turn: Have you experienced the doorway effect? What’s the most frustrating time it happened to you? Share your story in the comments below—we’d love to hear how you’ve tried to fix it. And if you found this guide helpful, pass it along to a friend, coworker, or family member who’s always forgetting tasks when walking through a door!